Visit any atheist website or Facebook group and you’ll quickly discover that atheists pride themselves on being the white knights of equality and the moral guardians of human rights. Yet their own worldview — evolutionary materialism, the understanding that humans are an unintended byproduct of time plus chance plus matter — gives absolutely no basis for such lofty ideas as equality and human rights.

This was demonstrated perfectly during the recent debate between Christian philosopher William Lane Craig and the chair of Atheist Ireland, Michael Nugent, who, during the Q&A, casually asserted that human life is no more valuable than animal life.

For most people, this is a deeply disturbing idea. But Nugent, to his credit, was only being logically consistent. If there is no God, then he is completely correct; human life is literally no more valuable than animal life (or any other form of life, for that matter).

Here’s the logic:

- There is no God; all life is the product of time plus chance plus matter.

- As such, humans exist on an unbroken continuum with animals. They are Darwinian primates, nothing more, nothing less.

- Therefore, human life is no more valuable than any other form of animal life.

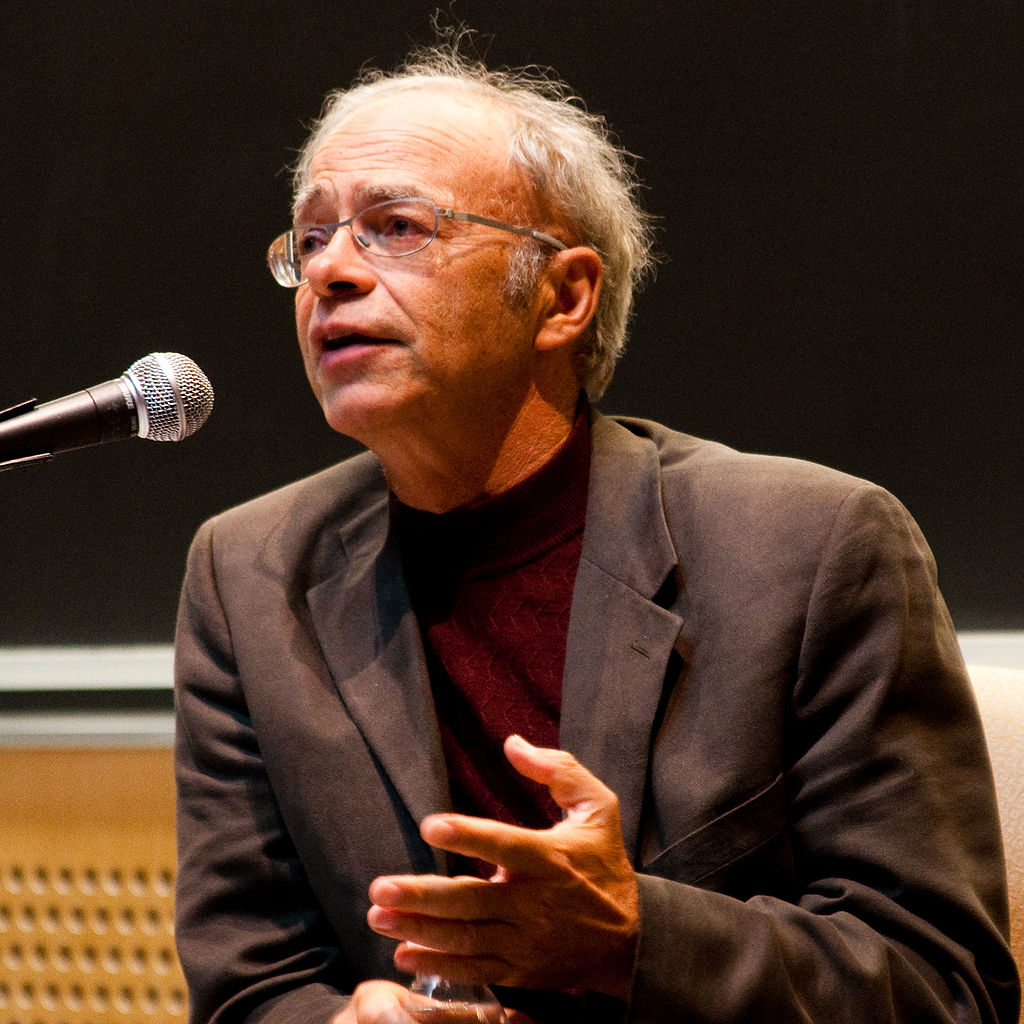

Nugent is not alone. Peter Singer, a committed atheist and one of the world’s leading ethicists, put it this way during this TV interview:

“Why do you think a member of the species Homo sapien, just because they’re a member of that species, has a right to life that, for example, a non-human animal – let’s say the gorilla who was shot in Cincinnati Zoo last week – does not have? Even though the gorilla has far more self-awareness, far more ability to form relationships with others, than a member of the species Homo sapien with severe brain damage.”

So where does this idea of human equality from?

Nancy Pearcey writes that Alexis de Tocqueville, a 19th-century political thinker, believed the idea of human equality came from Christianity:

“The most profound geniuses of Rome and Greece never came up with the idea of equal rights. Jesus Christ had to come to earth to make it understood that all members of the human species are naturally alike and equal.”

For a more contemporary example, atheist philosopher John Gray, states:

“Darwin has shown us that we are animals,” and therefore “the idea of free will does not come from science. Instead, its origins are in religion — not just any religion, but the Christian faith against which humanists rail so obsessively.”

How do atheists account for human rights and human value if they reject Christianity?

Not coherently. Without the understanding that every human is, by nature, intrinsically valuable, atheists have to contrive another set of criteria that human beings must meet in order to be considered worthy of rights. We see this most prevalently today with secular arguments for abortion, where an unborn human must be, amongst other things, “viable” and “sentient” before she can be considered worthy of life. Merely being human is not enough.

Indeed, being born isn’t necessarily enough, either. Singer goes as far to recommend a 28-day quibble-free return on newborns, “My colleague Helga Kuhse and I suggest that a period of 28 days after birth might be allowed before an infant is accepted as having the same right to life as others.” Again, he’s being perfectly consistent because, when you think about it; newborns also fail to meet the standard of viability and sentience that are set for the unborn.

Infanticide apologist Peter Singer. Good job he’s not a leading ethicist who advises governments or anything. Oh, wait.

For atheists, then, human value is determined subjectively by those in power, depending on what their particular culture believes during whatever time period they happen to live in. For intellectually honest and logically consistent atheists, like Singer, this means that the value of a human life can sometimes be even less than that of an animal’s — which is why some atheists can be, without any sense of irony, both pro-choice and vegan. Save the whales, kill the babies, if you will.

Scary biscuits, isn’t it? Perhaps not if you agree with those in power, or you just so happen to satisfy the requirements necessary to be granted rights. But if the powerful are the ones who give humans their value, they can also take it away. As we see with what is happening to gay men in Chechnya, there is nothing to stop those in power from reimagining the line between human value and animal value to something the atheist doesn’t like. One society says the unborn have no rights, another says gays have no rights. Which one is wrong? Says who?

Atheism and human rights are completely incompatible

Of course, this doesn’t prove atheism wrong (we can appeal to other arguments for that), nor does it mean that atheists cannot be capable of great moral deeds, but it does prompt the question: which view is better equipped to answer our deep intuitions that we should care for the weak, the oppressed, and the disabled? The view of Michael Nugent, who belives that humans are no more valuable than rats? Or the view of Helen Rosevere, a Christian missionary whose belief that all human beings are created equally compelled her, under pain of rape and civil war, to practice medicine and establish hospitals in the Congo?

Thankfully, atheists are an inconsistent bunch. Even if they are willing to openly express the view that human beings are nothing more than moist robots that have no more value than a fruit bat, none of them actually live like they believe it (being a vegan doesn’t count because Plant Lives Matter too). To be a good atheist is to be a bad atheist.

As Christians, we need to call them up on this. Human equality and the idea of intrinsic human value are the logical outworkings of Christianity. And if atheists wish to hold consistently to these ideas, they must abandon their atheism. They can’t have it both ways.

The problem with Singer’s take on ethics (as described here) is that it requires one to look no further than one’s nose for one’s guiding principles.

While it tries to appear lofty and thought-through, it actually reduces ethics to a guiding consensus formed around a range of permissions that are rooted in convenience rather than objective principle. Baby not up to par? Send it to the gas chamber! And so on.

There is no appeal to any overarching principle, nor does there seem to be any thought for the consequences.

It is not difficult to imagine, for example, that if infanticide were to be made legal on the proviso that it had to take place under the auspices of doctors, there might very quickly be no crime of infanticide, full stop, as the courts would find it increasingly difficult to enforce the law against people who took matters into their own hands. The moral basis of the law of infanticide would be significantly undermined if euthanising babies was legalised on the basis that they are not worthy of full personhood.

It is bizarre (albeit entirely congruent with easily observable traits of human nature) that atheists so frequently claim the moral high ground, while being so much closer, in philosophical terms, to having innocent blood on their hands.

I would far rather be in the care of Christians than leave myself (or children, if I had any) to the tender mercies of committed atheists.

Great comment!

Just wanted to pick up on your last statement. We are all, as you put it, moral piggybackers – unless we create our own philosophical viewpoints, devoid of any outside influence, we have morals which we ‘piggyback’ off others – whether it be a particular philosopher, or indeed religion. It’s a small point, but I’m nothing if not pedantic ;).

Slightly more importantly however, your view that human rights have “Christian-specific origins”. I’m genuinely interested as to how you come to this conclusion. If we take human rights as being those described in the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, I personally can see none to which Christianity can claim to be the sole proponent. If there is another such charter which outlines are human rights, and DOES have at least some for which Christian teaching is the sole basis, I’ll be happy to hear of it.

Finally, I’d like to attempt to answer your rhetorical question “So how do atheists account for human rights?” – just ’cause I’m that kind of person. I personally (and obviously I can’t speak for all atheists) account for these through the basic principle of “do unto others as you would have them do unto you” – the exact words of the Bible there by the way. Yes, this is a Christian principle. But it is certainly not an EXCLUSIVELY Christian principle. Take, for example, the societal concept of xenia in ancient Greece, a social more which dictated that one must open one’s doors and offer food/water to anyone who asked for it. People abided by this in the hope that, in their time of need, strangers would do the same for them. Yes, I may be ‘morally piggybacking’ this from Christianity, but if I am Christianity has done the same in taking it from Greek society, and they from early hunter-gatherers.

In summary, we treat each other equally, and – for want of a better word – ‘grant’ these rights to each other in the hope that they will be reciprocated. It is a simple mechanism by which we greatly enhance our quality of life, and the chances that we will survive and reproduce. By affording others these rights, we can ourselves expect to be treated in accordance with the same rights. I therefore account for human rights through the idea that they improve our chances of survival, the most basic of all facets of human nature.

Cheers, Daniel

Basically you are saying if something dented your chances of survival, they are dead meat. Find it funny atheists keep mentioning the survival of species as it suggests a meta ordinate level of group consciousness… That they profess doesn’t exist.

Funny that